The other day, in a colleague’s English class, we read one of my favorite poems by one of my favorite poets. Robert Frost – his very name evokes the natural – has a way of hooking my heart with profound confessions wrapped in the simplest of scripts.

Listen.

Desert Places

Snow falling and night falling fast, oh, fast

In a field I looked into going past,

And the ground almost covered smooth in snow,

But a few weeds and stubble showing last.

The woods around it have it – it is theirs.

All animals are smothered in their lairs.

I am too absent-spirited to count;

The loneliness includes me unawares.

And lonely as it is, that loneliness

Will be more lonely ere it will be less –

A blanker whiteness of benighted snow

With no expression, nothing to express.

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stars – on stars where no human race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

Frost was only 59 when he wrote Desert Places. There was a time in my life that I considered that age to be ancient; no more.

Lately, I find myself moving things that previously occupied some cupboard space down low – the cat food under the sink, charging cords, frequently used kitchen utensils – to places up high, more easily accessible, places that require no stooping or bending on my part.

I have begun to forget words, names. Sleep poorly. Find more strands in my hairbrush that I care to admit.

I age and age and age, in one direction only, fast, oh, fast, fighting those lonely places within myself that stick like stubble out of the soil of my soul.

Some days it’s even a struggle to work up the energy to ask for help – for Him to undull my heart, offer peace, or even acceptance. Perhaps it is enough to ask Him to simply sit with me, for I know that there is no place where His love isn’t.

I learned recently that the cells of a child live on in the mother long after the child is born. There is an exchange, and it has a name.

Fetal microchimerism “refers to the transfer of the baby’s genetic material into the mother’s body long after the birth of the child” (cradlewise.org).

Whoa.

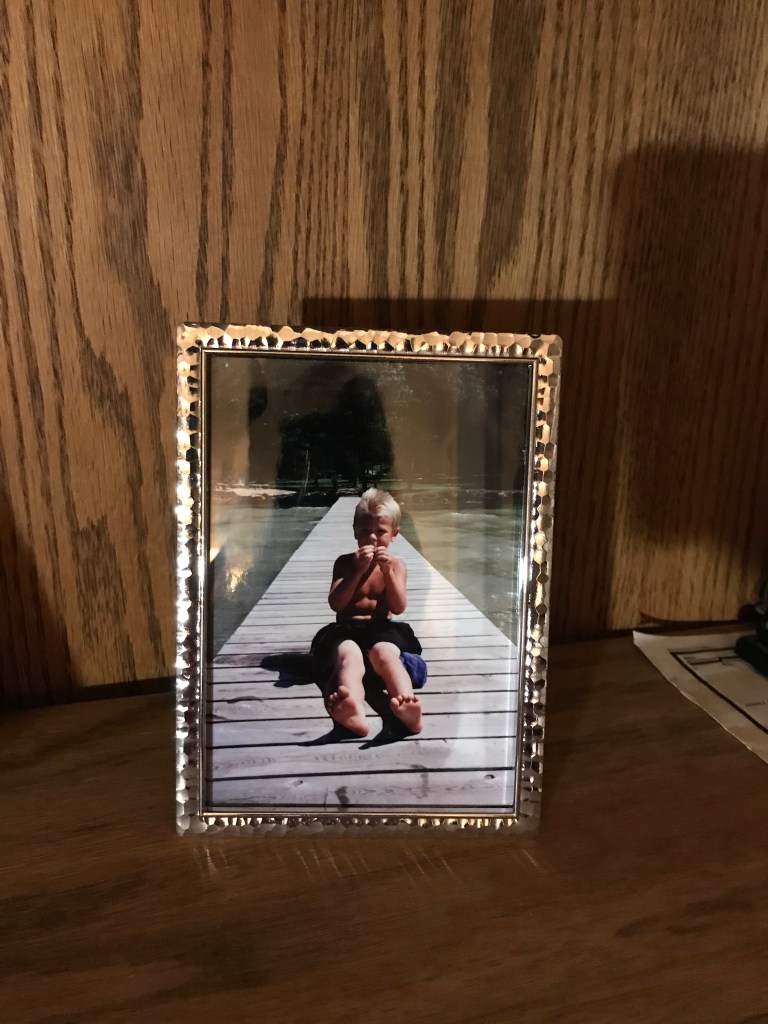

I think of my boy, the one I lost. He’d be 31 soon.

I often wondered where life went when it was all lived up. Heaven, yes, eventually, when He returns. But where is he now, my son?

To know that a part of him lives on, in me – an ever-beaming glow that never ages, coming to my rescue even though I could not rescue him – this is a gift.

Because here’s the thing: I also learn that those cells, those tiny baby cells, have the capacity to embed themselves in their mother’s tissue and actually repair harm.

Baby cells, like stem cells, can grow next to liver cells or bone cells, differentiate themselves, heal whatever’s around them.

The brain that remembers so slowly now, that jumps and skips and pauses unbidden; the heart that tears, remembering too well – bid my son’s, bid all my children’s cells, to draw near and help.

Do cells sing?

Mine must, united, now, as they are.

There is no need to scare myself with my own desert places.

I know someday all will be made well – my son’s mangled body, my own mangled heart.

Until then, there’s plenty of company, inside.